Why Performance-Based Funding is Reshaping How Money Flows

Performance-based funding is a system where money is allocated based on achieving specific results, not just enrollment numbers or operational costs. Instead of simply funding programs or institutions because they exist, this model rewards measurable outcomes like completion rates, employment success, or other defined goals.

Quick Overview:

- What it is: Funding tied to specific performance metrics rather than traditional inputs

- Where it’s used: 30+ U.S. states for higher education, increasingly in business services

- How it works: Institutions or providers receive money based on hitting benchmarks (e.g., graduation rates, employment outcomes)

- The goal: Drive accountability, improve results, and align spending with strategic priorities

- The trade-off: Can improve focus but may create unintended consequences if poorly designed

This approach has become increasingly popular as governments and organizations seek greater accountability for taxpayer dollars and client investments. In the U.S., versions of performance-based funding operate in at least 30 states, though research shows mixed results: modest improvements in some areas, but potential harm to equity and access for disadvantaged students.

The core idea is simple: pay for results, not just effort. But as we’ll explore, the execution is far more complex. The metrics chosen, the amount of funding at stake, and how the system handles different institutional missions all matter enormously.

I’m Santino Battaglieri, and through my work at SFG Capital, I’ve seen how Performance-based funding principles can effectively align service providers with client success, particularly in complex areas like Employee Retention Credit advisory where outcomes directly determine value. This experience has shown me both the power and the pitfalls of tying funding to measurable results.

What is Performance-Based Funding (PBF)?

At its heart, Performance-based funding (PBF) is a paradigm shift in how we allocate resources. Traditionally, funding for public services like higher education often relied on input-based models—think budgets based on student enrollment numbers, faculty salaries, or operational costs. The assumption was that if you provided enough resources, good outcomes would naturally follow.

However, PBF challenges this assumption by shifting the focus from what goes in to what comes out. It’s a system where a portion of a state’s higher education budget, for instance, is allocated according to specific performance measures, rather than solely on enrollment figures. This means institutions are rewarded for achieving tangible results, whether that’s graduating more students, improving retention rates, or successfully placing graduates in high-demand jobs.

This model has seen widespread adoption across the United States. As of a 2022 report from the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association, at least 32 states now use some form of PBF for institutions in at least one sector. This widespread accept signals a growing desire to ensure that public investments yield clear, measurable benefits. For us at SFG Capital, we see these same principles applying to how businesses seek specialized services, demanding clear outcomes for their financial commitments.

The Core Principle: Paying for Results, Not Just Efforts

The fundamental idea driving Performance-based funding is simple yet powerful: we pay for results, not just for the effort expended. This principle resonates deeply in both the public and private sectors. For state governments investing in higher education, it’s about ensuring taxpayer dollars translate into a skilled workforce and a thriving economy. For businesses engaging service providers, it’s about seeing a clear return on investment.

This approach introduces a strong element of accountability. When funding is tied to outcomes, institutions and service providers are incentivized to be more efficient and effective. It pushes them to critically examine their processes, identify areas for improvement, and innovate to achieve the desired results. This focus on value for money helps to build public trust and ensures that resources are directed towards programs and initiatives that demonstrably work.

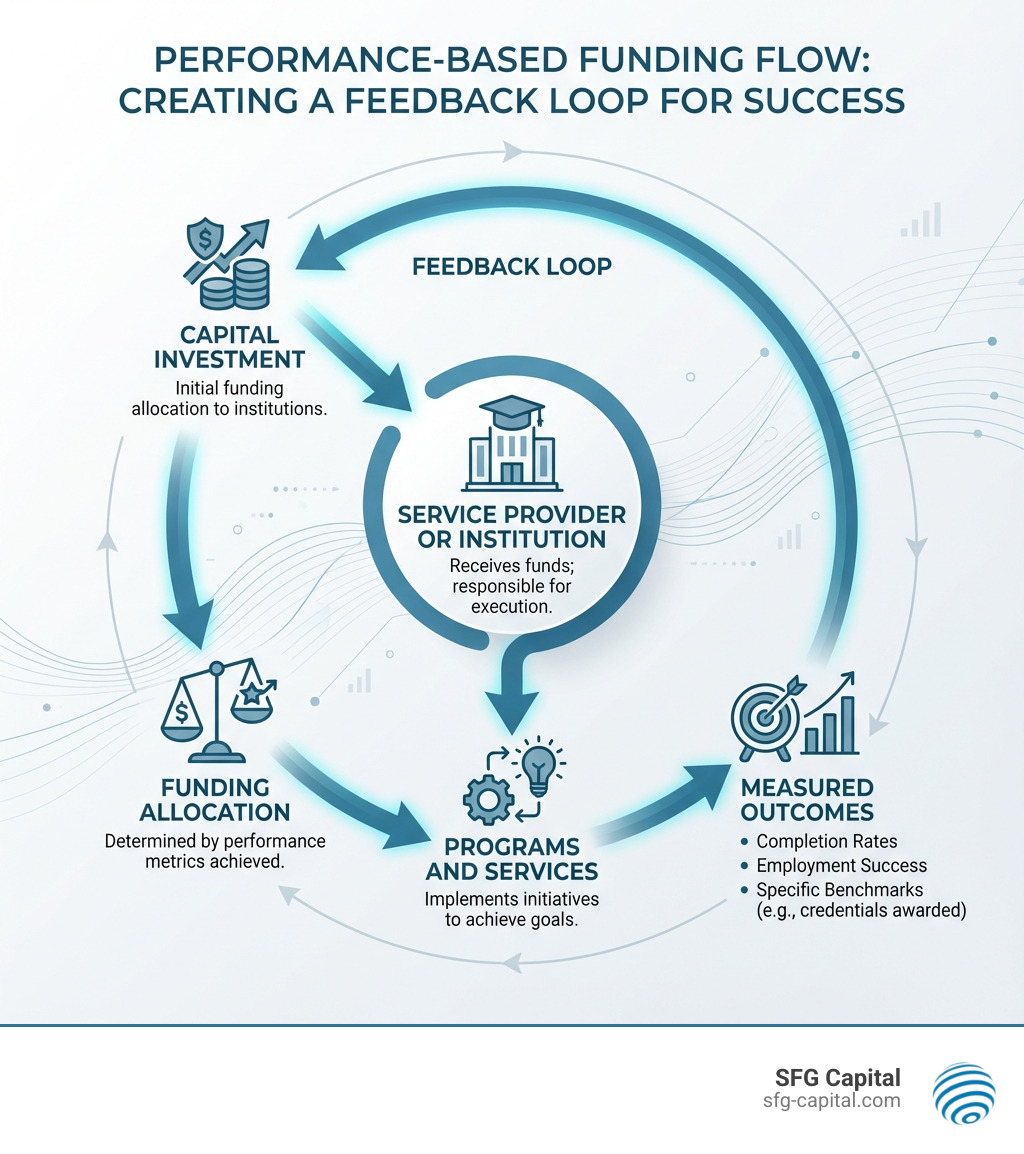

PBF is about aligning goals. When the funding mechanism directly rewards the achievement of specific objectives, the incentives for the recipient become perfectly aligned with the strategic needs of the funder. This creates a powerful feedback loop, encouraging continuous improvement and a relentless focus on what truly matters.

How Performance-Based Funding Models Work

Performance-based funding models are not one-size-fits-all; they come in various forms, but they all share the common thread of linking financial allocation to measurable achievements. The mechanisms typically involve:

- Metrics and Indicators: These are the specific, quantifiable measures used to assess performance. In higher education, common metrics include course completion rates, student retention, degree completion, and post-graduation employment rates or earnings. For instance, some states track the number of degrees completed in specific fields like STEM, or the success rates of students from low-income backgrounds.

- Funding Formulas: States often integrate these metrics into a formula that determines a portion of an institution’s base funding. For example, a state might allocate a certain dollar amount for each degree awarded in a high-demand field or for each low-income student who graduates. The amount of funding at stake can vary significantly, from a small percentage to a substantial portion of an institution’s budget. In North Dakota, for instance, a high of 90.4% of operating funds are allocated through PBF.

- Performance Contracts: Less common but still used, these are agreements where institutions receive funding if they meet specific, pre-negotiated goals. This can provide flexibility but requires careful negotiation and oversight.

- Performance Set-Asides: In this model, a percentage of funding is set aside, and institutions compete for these funds by demonstrating how well they’ve met certain targets. It’s a competitive approach that rewards top performers.

- Benchmarks: Institutions are often required to meet or exceed predefined benchmarks for each metric. These can be absolute targets or improvements over previous performance.

The evolution of PBF in the U.S. demonstrates a learning curve. Early models, sometimes called “Performance Funding 1.0,” often involved small bonuses and common indicators. However, as insights grew, a shift occurred towards “Performance Funding 2.0.” These newer models are typically integrated more deeply into base funding, feature mission-weighted metrics (recognizing different institutional roles), involve higher funding at stake, and often prioritize “counts” (e.g., number of graduates) over “rates” (e.g., graduation percentage) to encourage growth.

A systematic review of 52 peer-reviewed studies published between 1998 and 2019 that examined outcomes of Performance-based funding in U.S. states concluded that PBF led to either no impact or a modest increase in retention and graduate rates. This highlights the complexity and the need for careful design.

For us, understanding these intricate funding mechanisms is crucial. At SFG Capital, we apply a similar rigor to our processes, ensuring every step aligns with the ultimate goal of securing our clients’ Employee Retention Credit (ERC) refunds efficiently. You can learn more about how we work and how our approach is designed for your success by exploring More info about our process.

The Goals and Rationale Behind PBF

The move towards Performance-based funding isn’t just an academic exercise; it’s a strategic decision by governments and organizations to achieve specific, high-level objectives. We see this driven by a confluence of factors, primarily the desire for greater accountability, improved outcomes, and a stronger alignment between public investments and economic needs.

Driving Accountability and Improving Outcomes

One of the primary drivers for PBF is the demand for greater accountability in the use of public funds. Taxpayers and policymakers want to know that their investments are yielding tangible results. In an era of fiscal restraint, every dollar counts, and PBF aims to ensure that funds are directed towards institutions and programs that are demonstrably effective.

This model helps to build public trust by providing clear, measurable indicators of success. It shifts the conversation from simply funding institutions to funding results. By tying funding to outcomes, PBF encourages institutions to be more transparent about their performance and to actively pursue strategies that improve student success. It provides a framework for continuous improvement, pushing institutions to identify areas where they can do better and rewarding them for achieving those improvements. The goal is to move beyond mere enrollment numbers and measure what truly matters: whether students are completing their education, gaining valuable skills, and succeeding in the workforce.

Aligning Incentives with Strategic Needs

Beyond accountability, PBF is a powerful tool for aligning the incentives of higher education institutions with broader state strategic needs, particularly economic development and workforce demands. States across the U.S. are keenly aware of the need to cultivate a skilled talent pipeline to support high-demand, high-paying occupations. PBF provides a direct mechanism to encourage this.

For example, states like Kentucky and Louisiana have implemented PBF models that explicitly reward institutions for producing graduates in STEM fields, healthcare, or other state-defined critical needs areas. In Kentucky, 35% of an institution’s state appropriation is awarded based on student success outcomes, including STEM and health credentials. Louisiana’s formula aligns with economic development and workforce needs, basing metrics on the number of students completing programs leading to high-demand jobs. Texas recently overhauled its community college funding formula (H.B. 8) to primarily fund based on the number of high school students completing dual enrollment courses, community college students transferring to four-year universities, and community college students earning credentials of value.

This strategic alignment ensures that public investments in education are not just about access, but also about relevance to the economy. It helps to address skill gaps, foster economic growth, and ensure that our educational institutions are responsive to the evolving needs of the job market. We believe this principle of aligning funding with economic needs is a crucial aspect of responsible governance and investment.

PBF in Practice: From Public Sector to Business Finance

While much of the public discussion around Performance-based funding centers on higher education, the underlying principles are highly adaptable and increasingly relevant in the business world. We’ve seen how the lessons learned from state-level implementations of PBF can inform and inspire more effective financial arrangements in the private sector, particularly in specialized financial services like those we offer at SFG Capital.

Lessons from Higher Education Funding

In the United States, PBF in higher education has a rich, albeit complex, history. Between 1979 and 2009, 26 states experimented with PBF, with 14 states eventually discontinuing their programs. This mixed record underscores the challenges, but also the potential, of this funding approach.

We’ve observed a clear evolution from early, often flawed models to more sophisticated “Performance Funding 2.0” approaches. These newer models tend to integrate PBF more deeply into base funding, use mission-weighted metrics, and allocate higher percentages of funding to performance to create stronger incentives.

Here are some common metrics we’ve seen in U.S. higher education PBF models:

- Completion Rates: This includes course completion, program completion, and ultimately, degree attainment.

- Retention Rates: Keeping students enrolled from one term to the next.

- Transfer Rates: For community colleges, successfully transferring students to four-year institutions.

- Graduate Employment Earnings/Workforce Participation: Tracking how many graduates find jobs and their starting salaries, often with thresholds (e.g., earning over $25,000+).

- Degrees in Specific Fields: Rewarding institutions for producing graduates in high-demand areas like STEM, healthcare, or other state-defined critical needs.

- Equity Metrics: Increasingly, models include measures for the success of specific student populations, such as low-income students, students of color, or adult learners. For example, Tennessee’s outcomes-based formula incorporates a 40% premium for adults and students receiving Pell Grants.

While these models aim to improve outcomes, research has shown mixed results. A systematic analysis concluded that PBF led to either no impact or a modest increase in retention and graduation rates. Some unintended consequences have also emerged, such as institutions becoming more selective in admissions to prioritize students more likely to complete degrees, and research showing that minority-serving institutions (MSIs) can be disadvantaged by these models. For instance, a 2015 study of Texas’s PBF program found that its metrics disproportionately did not fund community colleges with high percentages of disadvantaged students, potentially encouraging recruitment of only students likely to succeed.

However, there have been successes. Indiana’s model, which began with 1% of funding tied to outcomes and now stands at 6% of operational funding, saw a 22% increase in degree completion for “high impact degrees” between 2010 and 2015. Florida’s PBF model, with a total allocation of $560 million for its State University System in 2021-2022, emphasizes clear, simple metrics aligned with strategic goals, leading to a 14.5% 4-year graduation rate increase and a 20.7% increase in median wages for bachelor’s graduates in certain periods. Tennessee is often cited for its comprehensive outcomes-based funding, aiming for 100% outcomes-based funding and using a dual approach with an outcome-based formula for the bulk of funding and Quality Assurance Funding for bonuses.

These examples highlight that successful PBF implementation requires careful design, sufficient funding at stake, flexibility for different institutional missions, and clear, simple metrics, often with “stop-loss” provisions to prevent institutions from losing too much funding too quickly.

Applying the PBF Model in the Business World

The principles of Performance-based funding are not exclusive to public education. In the private sector, we see these models manifesting as performance-based fees, risk-sharing agreements, and incentive structures that tightly align the interests of a service provider with the success of their client.

Consider our work at SFG Capital, right here in Travis County, TX. We specialize in helping businesses expedite Employee Retention Credit (ERC) refunds. This is a complex area, often fraught with IRS delays and intricate documentation requirements. For us, a traditional fee-for-service model (charging hourly or a fixed rate regardless of the outcome) simply wouldn’t make sense, nor would it serve our clients’ best interests.

Instead, we operate on a performance-based fee model. What does this mean for our clients in Austin, TX, and beyond? It means we only get paid when we successfully secure their ERC refund. Our fee is a percentage of the funds we recover for them. This creates a direct, powerful alignment: our success is directly tied to our clients’ success. We are incentivized to be as efficient, knowledgeable, and persistent as possible because our compensation depends entirely on achieving the desired outcome – a successful, expedited refund.

This model is a clear application of PBF principles:

- Defined Outcome: The successful retrieval and expedition of the ERC refund.

- Clear Metric: The amount of the refund secured.

- Aligned Incentive: Our fee is directly proportional to the client’s financial gain.

- Risk-Sharing: We take on the risk of effort and administrative costs; the client only pays for a successful result.

Furthermore, we understand that “expediting” is key. Many businesses face immediate cash flow needs and cannot afford to wait for prolonged IRS delays. That’s why we also offer advances or buyouts, providing quick access to funds while we steer the IRS process. Our expert claim assistance ensures that the application is handled correctly, minimizing further delays. This comprehensive, outcome-driven approach is how we deliver value to businesses, embodying the very best of Performance-based funding.

The Pros and Cons of Tying Funds to Outcomes

Like any powerful tool, Performance-based funding comes with both significant advantages and potential pitfalls. When considering its application, whether in public policy or private business, we must weigh these carefully to ensure that the benefits outweigh the risks.

The Case for Performance-Based Models

We believe there are compelling arguments for adopting Performance-based funding:

- Increased Efficiency and Focus on Results: PBF forces institutions and service providers to concentrate on what truly delivers results. When funding is contingent on outcomes, every effort is directed towards achieving those specific goals, leading to more streamlined operations and less wasted effort.

- Innovation and Best Practices: The pressure to perform can spur innovation. Institutions might develop new teaching methods, student support services, or business processes to meet their targets. This fosters a culture of continuous improvement and the adoption of best practices.

- Rewarding Excellence: High-performing entities that consistently meet or exceed their targets are rewarded with more resources. This not only acknowledges their success but also allows them to expand their impact, creating a positive feedback loop for quality.

- Better Alignment with Stakeholder Goals: For governments, PBF helps align educational outcomes with workforce needs and economic development goals. For our clients at SFG Capital, our performance-based fee ensures that our goals are perfectly aligned with theirs: securing their ERC refund. This creates a partnership where both parties are invested in the same successful outcome.

- Transparency and Accountability: PBF models often require clear metrics and public reporting, increasing transparency about how funds are being used and what results are being achieved. This strengthens accountability to taxpayers, students, or clients.

Potential Drawbacks and Unintended Consequences

Despite its promise, Performance-based funding is not without its critics and challenges. We’ve observed several potential drawbacks:

- Gaming the System: When an indicator becomes a target, it can be manipulated. This phenomenon, known as Campbell’s Law, suggests that the more an indicator is used for decision-making, the more it will distort the process it was intended to monitor. For instance, institutions might focus on easier-to-achieve metrics, lower standards, or discourage students who might lower their performance averages, rather than genuinely improving overall quality. The risk of distorting metrics is a serious concern that requires careful model design.

- Narrowing of Focus: An overemphasis on specific metrics can lead institutions to neglect areas not explicitly measured, even if those areas are vital to their broader mission or societal benefit. For example, if only job placement rates are rewarded, valuable arts and humanities programs that foster critical thinking but may not lead to immediate high-paying jobs might be de-emphasized.

- Increased Administrative Costs: Implementing and monitoring PBF systems requires significant investment in data collection, reporting, and analysis. This can create an additional administrative burden and cost, potentially diverting resources from core activities.

- Equity Concerns and Impact on Marginalized Groups: Research in the U.S. has shown that PBF can exacerbate existing inequalities. If metrics prioritize completion rates without adequate support, institutions might become more selective, inadvertently disadvantaging students from low-income backgrounds, underrepresented minorities, or those needing more academic support. Minority-serving institutions (MSIs) have been found to be particularly vulnerable to funding losses under PBF models.

- Instability and Unpredictability: While intended to drive stability through performance, poorly designed PBF models can introduce funding volatility for institutions, making long-term planning difficult.

These potential drawbacks highlight the crucial importance of thoughtful design, continuous evaluation, and a willingness to adapt PBF models. The metrics must be comprehensive, fair, and truly reflective of desired outcomes, and the system must include safeguards to prevent unintended negative consequences.

Frequently Asked Questions about Performance-Based Funding

We often encounter questions about the practical application and effectiveness of Performance-based funding. Here, we address some of the most common inquiries.

What are the most common metrics used in performance-based funding?

In the higher education sector in the U.S., common metrics frequently revolve around student success and workforce readiness. These include:

- Completion Rates: This encompasses course completion, program completion, and, crucially, graduation rates for degrees and certificates.

- Post-Graduation Employment Rates: The percentage of graduates who find employment within a certain period after graduation.

- Earnings of Graduates: Often measured as median wages of graduates employed full-time, sometimes with a specific income threshold (e.g., earning $25,000+).

- Degrees in Specific High-Demand Fields: Incentives are often provided for producing graduates in areas like STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), healthcare, or other fields deemed critical for state economic development.

- Student Success for Targeted Groups: Increasingly, models incorporate metrics rewarding institutions for the success of low-income students, students of color, or adult learners, aiming to address equity concerns.

In the business world, particularly for services like ours at SFG Capital, metrics are often tied directly to financial outcomes or project milestones. For us, it’s the successful and expedited retrieval of Employee Retention Credit refunds for our clients in Travis County, TX.

Has performance-based funding been proven to work?

The evidence regarding the effectiveness of Performance-based funding is mixed, indicating that its success is highly dependent on its specific design and implementation.

Research from the U.S. suggests that PBF models have led to either no impact or only modest increases in student retention and graduation rates. Some states, like Indiana and Florida, have shown positive outcomes in specific areas such as increased degree completion in high-impact fields or improved median graduate wages.

However, many early PBF programs in the U.S. were discontinued due to design flaws, and concerns persist about unintended consequences. These can include institutions becoming more selective in admissions, potentially disadvantaging marginalized students, or focusing narrowly on metrics at the expense of broader educational missions.

PBF is not a panacea. It’s a powerful tool that can work when carefully designed, with clear, appropriate metrics, sufficient funding at stake, safeguards against unintended consequences, and a recognition of diverse institutional missions.

Can this model be applied to small businesses?

Absolutely! The principle of paying for results is highly applicable and, we believe, exceptionally beneficial for small businesses. In fact, it often represents a more equitable and risk-asharing approach for engaging specialized services.

For example, a small business in Austin, TX, might engage a marketing agency on a performance-based model, where the agency’s fee is tied to increases in sales leads or website conversions. Similarly, a business looking to optimize its energy consumption might pay a consultant a percentage of the energy cost savings achieved.

At SFG Capital, our own model for assisting businesses with Employee Retention Credit refunds is a prime example. We operate on a performance-based fee, meaning our clients only pay us a percentage of the ERC refund we successfully secure for them. If we don’t get the refund, they don’t owe us a fee. This eliminates upfront costs and aligns our incentives completely with the business’s success. It’s a transparent and fair way for small businesses to access expert financial services without taking on undue risk, especially when facing potential IRS delays. We believe this approach empowers businesses to pursue opportunities like ERC refunds confidently, knowing their investment is tied directly to a tangible, positive outcome.

Conclusion

Performance-based funding represents a significant evolution in how we allocate resources, shifting the focus from inputs to measurable outcomes. From state governments funding higher education to specialized financial services for businesses, the core principle remains consistent: we pay for results, not just effort. This approach promises improved accountability, greater efficiency, and a closer alignment of incentives with strategic goals.

While the journey of PBF in the U.S. higher education system has been marked by both successes and challenges, we’ve learned invaluable lessons about the critical importance of thoughtful design. The choice of metrics, the level of funding at stake, and the consideration of potential unintended consequences—such as impacts on equity or the risk of “gaming the system”—are paramount.

At SFG Capital, we wholeheartedly accept the power of Performance-based funding in our services. For businesses in Travis County, TX, seeking to steer the complexities of Employee Retention Credit (ERC) refunds, our performance-based fee model ensures that our success is directly tied to yours. We provide expert assistance and even offer advances or buyouts to bypass IRS delays, guaranteeing that you only pay when we deliver results. This commitment to outcome-driven partnerships reflects our belief in transparency, accountability, and delivering tangible value.

We invite you to find how our performance-based approach can benefit your business. Learn more about our services and find out More about our company and our commitment to your success.